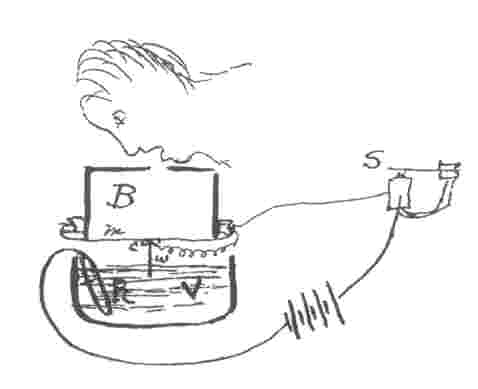

Bell’s Liquid Transmitter

Of all the early instruments devised and used by Bell and the other telephone hopefuls, Bell’s Liquid Transmitter is perhaps the most intriguing. It is also the one shrouded in a fair amount of mystery and mythology.

According to popular legend the instrument shown above was the device Alexander Bell used the afternoon of March 10, 1876 to make that historic phone call: “Mr. Watson, come here. I want to see you.” Unfortunately, it’s not true. This particular version was not made until some time after that date, and was then used by Bell for only a short period as he experimented briefly with a variable resistance transmitter. Only remnants of this model exist, and it is from these that all the replicas have been made.

The actual instrument Bell used that day was a rather crude device (see insert below taken from Bell’s laboratory notebook). It had been quickly assembled by his assistant, Thomas Watson, a few days after Bell returned from Washington, D.C., where he had just received his second patent for Improvements in Telegraphy (No. 174,465 issued March 7, 1876, the one historians would later label the most valuable patent ever issued). Notice that Bell was still using the reed receive as a listening device (see Gallows Model).

The operating principle of a liquid transmitter is quite simple. A wire attached to the bottom of a parchment diaphragm is adjusted so that it just barely makes contact with the water, which is made electrically conductive with a small amount of acid. Words spoken above the diaphragm cause it to flex up and down, making the attached wire have more or less contact with the acidulated water, thereby changing the circuit resistance. The resulting current variations in the listening device reproduce the original sounds. Properly set up, a liquid transmitter can transmit remarkably clear conversations.

Again, according to popular legend, that historic call was also the first time a telephone was used to summon help. Supposedly, Bell had spilled acid on his pants and, in his excitement, blurted out those historic words. Unfortunately, that also is part of the myth. Nowhere in his laboratory notes for that day does Bell mention spilling acid. Nowhere in the letter he wrote that evening to his father, detailing the historic events of that afternoon, does he mention spilling acid. And nowhere in Watson’s notes for that day is there any mention of spilled acid. Most historians today agree that, although it’s a charming story, it never happened.

As mentioned earlier, there is still

mystery and unanswered questions surrounding Bell’s Liquid

Transmitter. Why is there no illustration of this device in that

famous patent? Why is it so uncannily similar to the transmitter

shown in Elisha Gray’s caveat, filed the same day as Bell’s

patent application? Historians and researchers are still probing

for answers to these and other mysteries.

This page was written by A. Edward Evenson, Author of the book The Telephone Patent Conspiracy of 1876 available at Amazon.com

Return to the homepage

Interested in old telephones? Check out the Antique Telephone Collectors Association